Installation artist David Gappa reveals how grit guides his artistic evolution.

By Philip Hernandez

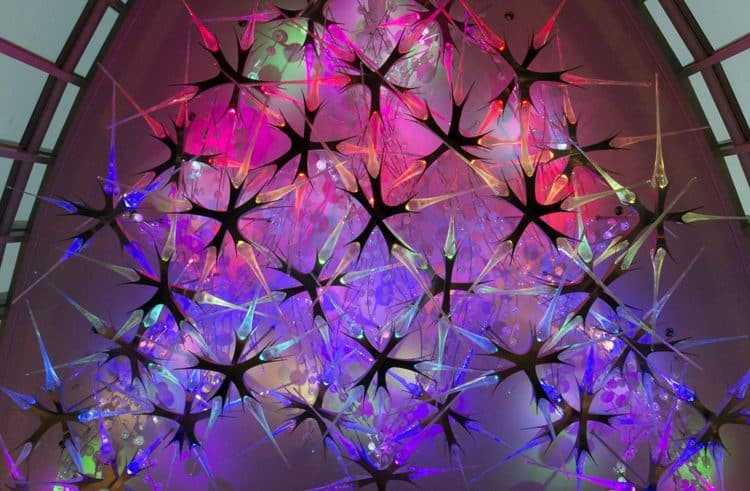

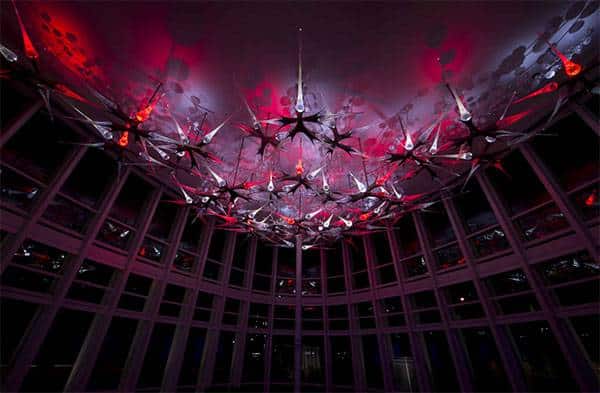

We depend on external talent to elevate our seasonal entertainment to new levels. The most successful projects are those that align the gritty artists’ ultimate concern with our project objectives. This alignment requires understanding what a gritty artist is, being aware of the artists’ ultimate concern, and communicating clear project expectations. Once we find an artist whose passion aligns with our vision, trust is the key to creating experiences that people never forget. David Gappa’s glass-and-steel installation, “Introspection,” exemplifies how this alignment and trust manifests in stunning results. In April 2017, “Introspection” was unveiled at The University of Texas at Dallas’ Center for BrainHealth. The work makes visible a hidden process that occurs in the body: the communication between nerve cells to capture the essence of thought as it pulsates through a field of synapses. Gappa was given free rein to explore new creative frontiers and challenge himself as an artist—which is how he defines grit. |

Introspection is an intricate, ceiling-installed sculpture in glass and steel that’s fifty feet wide, forty feet long, and weighs 5,300 pounds. It comprises one hundred and seventy-five LED-illuminated glass spires manufactured by Gantom and 1,050 hand-blown glass spheres. Each five-and-a-half-foot spire is individually illuminated and programmed to pulsate an array of colors across the entire piece, similar to the electric impulses passed from one nerve cell to another. Introspection is the focal point of the research institute’s multi-purpose room and serves as a visual reminder of the institution’s commitment to enhancing, protecting, and restoring brain health. |

Introspection is an intricate, ceiling-installed sculpture in glass and steel that’s fifty feet wide, forty feet long, and weighs 5,300 pounds. It comprises one hundred and seventy-five LED-illuminated glass spires manufactured by Gantom and 1,050 hand-blown glass spheres. Each five-and-a-half-foot spire is individually illuminated and programmed to pulsate an array of colors across the entire piece, similar to the electric impulses passed from one nerve cell to another. Introspection is the focal point of the research institute’s multi-purpose room and serves as a visual reminder of the institution’s commitment to enhancing, protecting, and restoring brain health.

Gappa’s Definition of Grit

Gritty artists have particular traits, as seen in David Gappa. “To me, grit is the willingness to dive into the unknown,” he replied. “To take a chance on something that you have no idea of where it will lead. To put the faith and talents that have been given to you into God’s hands and say, ‘Hey, you know what? Here I go and let’s see where it leads us.’” To David, this translates to a willingness “to dive into the heart of a 2400-degree furnace and take a chance on offering something to the community that they don’t need. To do his art, David gave up a full-time career as an architect with a steady paycheck and took on a six-figure loan. In my humble opinion, that’s grit—the faith and willingness to dive into something without having any idea where it will lead.

The Path to Grit: Discovery, Development, and Deepening

In David’s career path as an architect notice how he satisfied the three D’s that define grit—discovery, development, and deepening.Discovery

David said he’s always had an affinity for art. “As far back as second grade, I’d draw pretty routinely—stick figures and pretty pictures and Charlie Brown images and things like that. I was always the best at drawing Snoopy and Charlie Brown,” he said. At some point, his mother realized her son’s passion and enrolled him in classes at a local museum. Noticing David’s talent, one of those teachers started an experimental art program in which David participated. “They wanted a commitment from us to come in every Tuesday night, every Thursday night, and all day Saturday,” explained David. “That was pretty much my life from fourth grade until I was a senior in high school. It was awesome.”Development

David intended to be an engineer when leaving for college, but the left side of his brain wasn’t conducive to that world. “I was very frustrated, and one day I was walking across campus and happened to walk through the architectural department. I noticed these amazing three-dimensional models that these students had fabricated. I didn’t see them as buildings. I saw them as these amazing sculptures that just happened to be livable.” While David was working on a graduate degree in architecture, UT Arlington started a glass-blowing program. He took one elective in glass-blowing for fun and helped build the first glass-blowing studio on the campus. “This gave me an inside track into understanding the mechanics of a studio,” he said. David got his Master’s in Architecture and worked in an architectural firm for about 10 years. “I quickly came to realize that architects made these beautiful buildings, but only a small percentage of time was spent on the creative end of that. About 90% of the effort was spent pulling construction drawings together and fabricating and designing cross-sections in architectural details. There’s a beauty to that, as well, but I felt the creative end of it was severely lacking.”Deepening

David met another glass-blower while at the architectural firm and the pair opened a glass-blowing studio. Thus began five years of learning glass blowing while working full time as an architect. “I learned the basic mechanics of how to manipulate and form and harness this heat. Lots of late nights, lots of early mornings just having fun enjoying this part of it.” It was this deepening of his craft as well as his artistic vision that led to David’s confidence to try something entirely out of his experience and comfort zone—the ‘Skeletal Series,’ which were glass skulls of prehistoric animals, each of which took an entire day to create.

Developing an Ultimate Concern

Gritty people have a deep understanding of their ‘ultimate concern’ or long-term goal/purpose in life. Aligning a person’s ultimate concern with a project’s objectives creates extraordinary results. David made a conscious effort to hone the ultimate concern of his work, and it wasn’t easy. Early in his career, David teamed up with a partner and soon realized their visions weren’t the same. “We went through a hard time trying to work through those complications of different personality types. As a result, I eventually ended up buying that business partner out. I realized I needed to have a clear, concise direction as to what this vision of a glass-blowing studio needed to be—the merging of the art of glass in the interior or exterior space and the integration of my work in the community,” he said. “But there was nothing easy about that process,” stated David. “All of the sudden, I went from a partnership in which my partner was managing the studio during the day while I was there in the evenings to me having full throttle of this company while still working a full-time job elsewhere as an architect. That process of redefining myself and redefining my brand was a scary time for a good while because the dollars weren’t going to be coming in anytime soon. It took a while to develop that focus and convey it to my patrons and the general public.” Understand that gritty people have a vision for their life, and tap into it when you can. Grit Means Engaging in a Regular and Deliberate Practice of Scrutinizing One’s Craft Regular and deliberate practice—the intense scrutiny of one’s craft- sharpen talent. As David went through these changes, he was developing and deepening his relationship with glass blowing on his own. He was practicing regularly and making deliberate improvements. Deliberate practice involves focusing on one’s weaknesses and attacking them intensely. “I experienced that not too long ago. After years of stalling, I finally said to my team at the studio that we were going to dedicate an entire month to create a body of work that was outside our realm, was going to consume an enormous amount of time, and would be very costly. But I wanted to do this for my own edification and to push my limitations as an artist. What we created was something called the ‘Skeletal Series.’ It was a body of work in which we focused on mammoth skulls, T-Rex skulls, Triceratops, horseshoe crabs, Saber-tooth Tigers. These were extremely detailed, sculpted-glass pieces of artwork. Talk about a dedicated amount of time! Each one of these skulls took about seven or eight hours. When I say seven hours, that’s seven hours of sculpting glass in front of a 2400-degree furnace with three of your assistants there with you the entire time. I was the only one that didn’t get a break for those seven to eight hours. I was just powering down energy bars and water while I manipulated this glass one minute at a time for seven hours until that piece of work started to evolve.” David continued, “But this isn’t only about me. This is about any glass artist or any glass sculptor. True grit is the willingness to take that challenge head on, knowing that you’re going to invest seven hours and three assistants’ time with a 2400-degree machine burning the entire time and knowing that one mistake from any of those team members could mean that entire sculpture is lost. You always hope that if a mistake is made, that happens within the first two hours. If, six hours into it, something goes wrong, it’s all over,” he said. “Looking back, that was probably one of my most favorite times in my career. There was no monetary drive and no ego. It was all about doing something I’d never done before. It was awesome.”

“Looking back, that was probably one of my most favorite times in my career. There was no monetary drive and no ego. It was all about doing something I’d never done before. It was awesome.”

The Importance of Hope—and How to Maintain It

Hopelessness is suffering we believe we can’t control. I asked David if he ever felt hopeless, and how he got through that. “I think most entrepreneurs, at some point, realize they may have tackled something larger than what they can handle. After taking on a substantial loan, diving into this uncharted world of glass, and then trudging through the learning curve of not knowing enough about glass and even less about business and marketing, I certainly had my hopeless moments,” he confessed. “I realized very quickly at the beginning that I couldn’t pay my staff. I can’t tell you how many years my family barely made ends meet. We got to the point where we were on Medicaid to support our third child and took out a second loan to make payroll. We had two businesses—the studio, which needed to be managed, and a gallery connected to the studio that required a full-time staff. It got hairy for several years and made me seriously question whether I’d made the best move for my family. My father thought I was nuts, but he was also supportive. He helped me out with the first loan,” he said. “What brings you through those times is knowing you have support from your family, your friends, and from God. You spend much time in prayer asking for guidance and discerning that this is where you’re supposed to be. There was never a doubt that I was going to push through it. However, the one thing that tears any entrepreneur down is fear. I spent many, many hours in prayer just fighting that fear. I’d say to myself, ‘I’ve got three kids, a wife, and I’m an artist that creates something that’s not needed at all.’ All of the rational parts of my brain were telling me this isn’t a good move and I should go back to architecture where there’s a steady income. After hours of discernment, I was able to reflect on the direction I chose in life and decided I had to either make it or break it. Thank God we’re still ticking and moving forward.”

How to Work with a Gritty Artist for the Best Results

The “Introspection” installation shows how matching a project with an artist’s ultimate concern can result in a stunning creation. In the attractions industry, if we bring in an artist to work on a project and we don’t have a full understanding of what their ultimate purpose is and what they’re gritty about, we’re not going to get the best result in that project. We asked David for his suggestions about how to work with a gritty artist—especially if you’re gritty yourself—to create a successful project. “Some artists can create a specific portfolio of work, and that’s all they do… The client needs to understand the artist isn’t going to diverge from that particular design paradigm. I take pride that I don’t have a specific design paradigm. I view a space as an open canvas. If a designer comes to me and tells me a space is going to accommodate brain surgeons for the Center of BrainHealth… I still cringe a little in the depths of my heart because I wonder if this designer will allow me to implement my creative thought processes within that space, or do they want to control everything,” he said.The Bottom Line—You Have to Trust the Artist and Let Them Do Their Thing

Some artists have their Ultimate Concern figured out, and they understand how their craft serves it. They’re very clear about it, and that makes it easier for those of us in the attractions industry who are working with them to align. The most successful projects are those that include the intersection of these two mindsets in which what we need supports what the artist is trying to accomplish. We asked David to comment on this. “It comes down to having trust in the artist to execute. I’ve had that trust very rarely,” stated David. “One of those times was with the ‘Introspection’ installation I did at The Center for BrainHealth. I worked with Sandra Chapman, the President of the Center. This was a benchmark installation, and Sandi’s faith meant a lot. She told everyone, ‘David Gappa is the artist, and he’s going to make this happen.’ Of course, having that control means much anxiety about meeting the client’s expectations. However, Sandi was the perfect client. Of course, there were still complications with the manufacturing of the installation, but everyone—the team at Gemini Lighting and, of course, Gantom—all came through. The team at MP Custom Fabrication worked an enormous number of hours to make the steel armatures of the synapses and the steel structure on which were mounted all these thousands of spheres. They also fabricated all of the steel substructures above the ceiling that no one sees.” Dr. Chapman made this commented about David’s fabulous installation, “We wanted something to awe you because the brain likes to be awed. It changes the neurotransmitters.” Gappa’s installation definitely inspires awe. Co-creators of “Introspection”

MP Custom Fabrication |

Gemini Lighting |

Gantom Lighting & Controls |

|

Gappa also wanted to give kudos to the studio staff who assisted with Introspection. “It takes an army to create an installation like this, and I don’t take any one of those key components for granted.” |

Key Takeaways:

- We depend on external talent to elevate our seasonal entertainment to new levels. The most successful projects are those that align the gritty artists’ ultimate concern with our project objectives.

- Identifying Gritty people is tough, but there are markers: clear vision/ultimate concern, development and deepening of passion, deliberate practice, and hope.

- Ultimate Concern: “I realized I needed to have a clear, concise direction as to what this vision of a glass-blowing studio needed to be—the merging of the art of glass in interior or exterior space and the integration of my work in the community. That process of redefining myself and redefining my brand was a scary time for a good while because the dollars weren’t going to be coming in anytime soon. It took a while to develop that focus and convey it to my patrons and the general public.”

- Deliberate Practice: “Looking back, that was probably one of my most favorite times in my career. There was no monetary drive and no ego. It was all about doing something I’d never done before. It was awesome.”

- Hope: “After taking on a substantial loan, diving into this uncharted world of glass, and then trudging through the learning curve of not knowing enough about glass and even less about business and marketing, I certainly had my hopeless moments.”

- In the attractions industry, if we bring in an artist to work on a project and we don’t have a full understanding of what their ultimate purpose is and what they’re gritty about, we’re not going to get the best result in that project.

About The Author

Philip Hernandez

Philip Hernandez is a freelance writer, speaker, producer, and marketer specializing in Seasonal Attractions.

In 2018, Philip became the CEO at Gantom Lighting & Controls, a manufacturer of the world’s smallest DMX LED lighting. Gantom is used in every major theme park worldwide to illuminate where other fixtures cannot.

Since 2014 Philip has published Seasonal Entertainment Source magazine (SES), a quarterly print publication for the seasonal attraction professional. SES ships to readers in over 18 countries.

Philip operates the Haunted Attraction Network (HAN), the largest global media entity for the haunted attraction industry. HAN includes written content, videos, a series of podcasts, and the Haunt Design Kit brand.

Philip produces the Leadership Symposium for Seasonal Attractions, a masterclass series for seasonal attraction professionals. Watch more here.

Philip co-hosts the ‘Marketing your Attraction’ podcast monthly. Listen here.

Contact Philip for projects here: [email protected]